Sterling MA Now Has Its Own Little LAMB Fiber Network

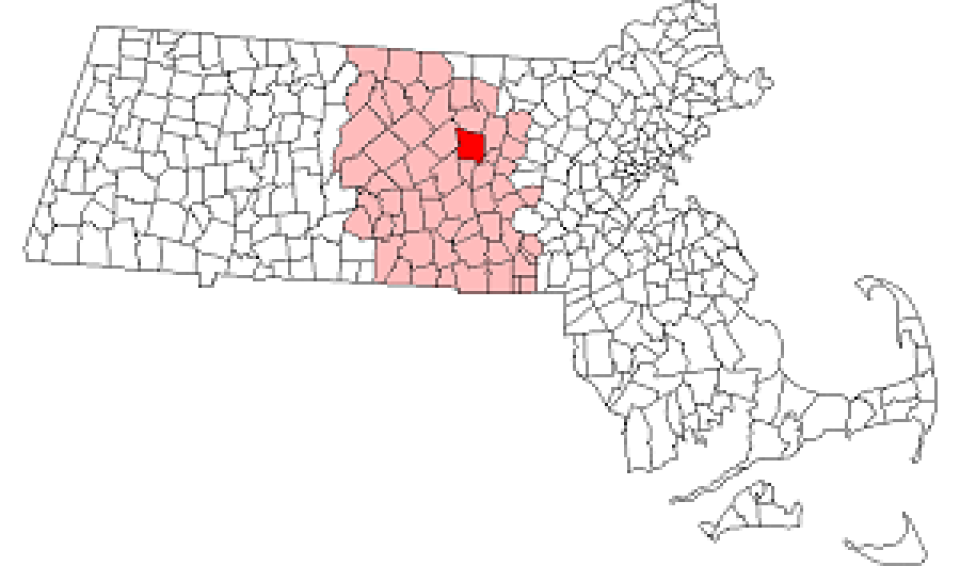

As communities across the Commonwealth of Massachusetts are at various planning stages in laying the groundwork to build their own municipal broadband networks, a rural Bay State town about 50 miles west of Boston has moved past the planning phase and is now offering municipal fiber-to-the-home (FTTH) service.

In Sterling (est. pop. 8,000) – the town that lays claim to Mary Sawyer Tyler, said to have inspired the “Mary Had a Little Lamb” poem – the town’s municipal utility is building out its aptly named Local Area Municipal Broadband (LAMB) network.

The project was initiated more than five years ago as a new division within the century-old Sterling Municipal Light Department (SMLD). As one of about 40 of the state’s 351 towns and cities with its own municipal electric utility, SMLD was awarded a $150,000 state grant to help finance the construction of a 23-mile regional I-Net ring in 2020. A year later, LAMB lit up its first residential customer in April of 2021.

Following an incremental approach, earlier this year, the LAMB added its 50th subscriber as construction crews are on track to build out a town-wide fiber network by the end of 2024.

Connecting with Nearby Towns

Like other communities across the nation with an established municipal utility, from a design and engineering standpoint, it was a relatively easy leap into broadband for SMLD, which currently supplies electricity to more than 3,700 residential, commercial and municipal customers.